Who is your favorite historical figure?

This long dead Elizabethan is the major obsession of my adulthood – as opposed to several more fleeting fixations. The 419th anniversary of his death falls tomorrow so when I saw the daily prompt today I had to answer it.

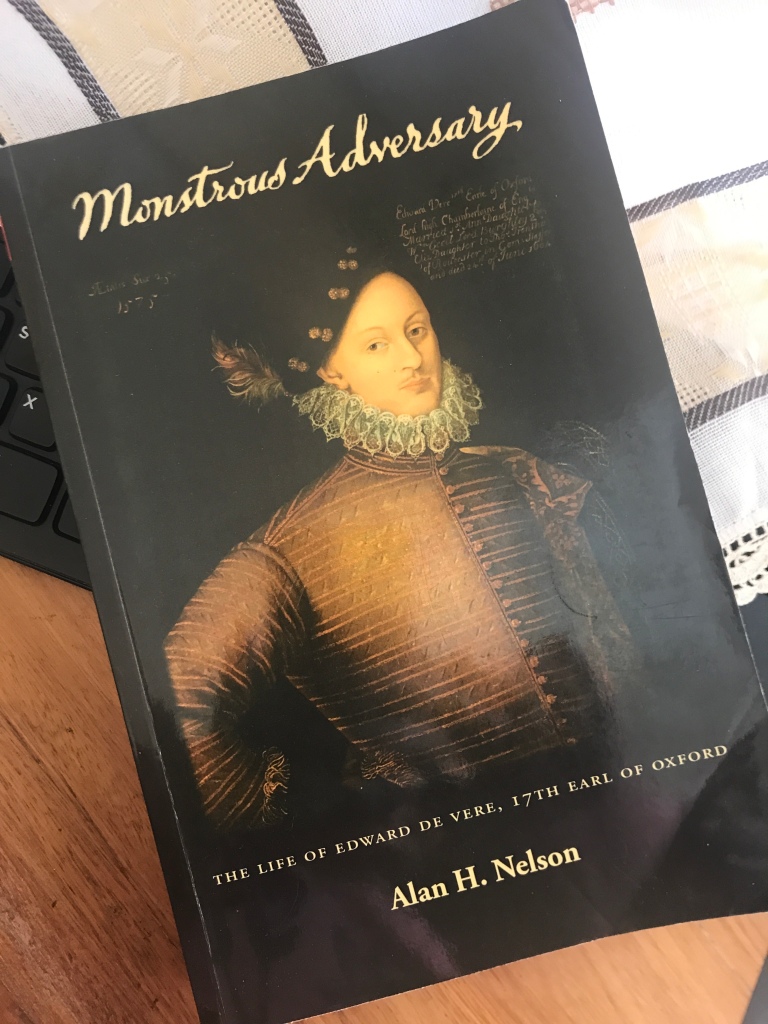

The man who signed his name Edward Oxenford is better known today as Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. If he is remembered at all it is by those engaged in the Shakespeare Authorship Question and is considered by many as the most likely person to have written Shakespeare’s works outside of Shakespeare of Stratford.

But why doubt Shakespeare wrote the works ascribed to him?

The most glaringly obvious reason is the works themselves: they are written for the enjoyment of the aristocracy of his day and most tellingly, they are on the side of the aristocracy. The portrayal of the working classes is: often disrespectful e.g, his dumb mechanicals; is not written from a place of understanding and empathy; can be idyllic in the pastorals although as representations noted by an outside observer.

The plays are often written in poetic verse with rich sub-texts – a form of art for those who have the education and time to decipher and enjoy them.

They works demonstrate knowledge of the law, foreign languages, classical texts, contemporary European geography, hunting hawking, gardening and music that would be enviable in one educated man but incredible, as in, in-credible in a working man of little or no education.

A mind and body chasing commercial success in agriculture, and in the investment side of theatrical enterprise wouldn’t have had the time to devote to conceiving and writing the canon of works ascribed to Shakespeare. This mind could not have belonged to the man who signed his name 6 or 7 times, Shakspere, with different spelling forms, and never as Shakespeare.

But this is only the beginning of why I’m fascinated with him.

He polarises people. He was a poet, patron of the arts, a paedophile who kept a company of boy actors, a deadbeat dad and inattentive husband, a love-cheat, a recusant, a manslaughterer, and a vain dandy and an aristocrat. Who would want him to supplant the Cinderfella from Stratford? Even his biographer couldn’t bring himself to write a sympathetic account of his life.

Who would want him to supplant the Cindefella from Stratford?

The prismatic thoughts, arguments, admiration, disgust and awe that he inspires fascinate me. Here are some of the questions that have prompted me to question any research into him that I do.

He was accused of paedophilia in a court of law. Did he? Didn’t he? Should a writer’s biography be taken into account when enjoying the product of his mind?

Are the works of an artist necessarily biographical? Should we read back from the works to understand the writer’s life. Something some who have tried to fill the gap in the historical record have fallen victim to.

If we continue to want to idolise Shakespeare, is it better to maintain the myth of the man from Stratford than uphold the truth of a man who committed many sins.

Can we forgive a person his sins – heinous though they be- if the product of his mind transcends them?

Can we not separate the works from the man?

What if the works were a group effort? Would they be less important if they were the product of many minds and not that of a genius?

Was he a genius? Should that excuse his greater sins? Should a genius or person held up as an example be perfect? Even the saints weren’t.

Why do we need to idolise Shakespeare? Why do we need heroes?

Is the search for Shakespeare really a subliminal search for self or God? If I am a group-theorist (many writers produced Shakespeare’s canon) does that make me a pagan with a prismatic pantheistic need?

He lived so long ago, does it even matter?

If he took pains to conceal his identity are we being disrespectful by trying to expose the fraud?

Does the long-dead truth matter?

Who will benefit from the truth and who will lose?

Should the myth be protected?